Always Worth a Second Look, the Benefits of Time and Digitization

January 7, 2013 Leave a comment

Sometimes, the most helpful resource is a newer format of an old standby.

As Finding Aids & Beyond returns for the new year, I’m inspired to look back at some old resources that have only improved with the benefits of time and digitization. For example, historic newspaper collections like Chronicling America — new data mining tools enable you to comb the pages for trends as well browse articles. Good content, whatever its format, is always worth a second look.

My email, Facebook, Twitter, etc. constantly are inundated with alerts about hidden collections made accessible, newly published exhibits, and digital content updates, not to mention new history apps. Inevitably, I file away the newest thing for future reference only to rediscover it during an impromptu online search. Or it pops up on my radar as a part of a complied list or bibliography. At first, I was uncertain how to resolve this redundancy. Now, I have come to recognize it as a valuable step in the research process — to make new connections between disparate sources and reevaluate conclusions drawn from existing sources.

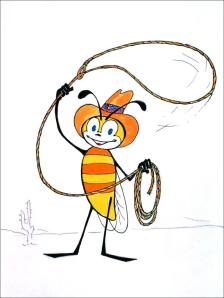

CDC’s Wellbee

When searching for information, especially on a familiar topic, there are benefits to going back through sources for a second and third look. This is particularly true of online sources, which may have changed in format if not content since your last visit.

Case in point — I always forget about the CDC’s Public Health Image Library. Maybe this is because it is a smaller collection, but the database is still a great place to find clip art as well as historic gems, like the Wellbee cartoon first used in the 1960s during the Sabin oral polio vaccine campaigns in the United States. When it went out West, the Wellbee donned a ten gallon hat and a lasso!

Another example of the benefits from giving past resources a second look came recently when I was working on an article about field nursing during the Great Depression. I had not worked on the topic in several years and was coming to the material with new and different interests. I found new photos, newspapers, and entire folders-worth of documents that had previously been unavailable. It was a goldmine.

Digitized primary sources, like those in E-Archives, allowed me to do research that was impossible five years ago without significant time and expense. Special mention goes to the digital gallery at Cline Library’s Special Collections and Archives at Northern Arizona University. I had not been able to visit this particular archive on past research trips but knew about its valuable collections, particularly related to the Four Corners region, because of the finding aids included in Arizona Archives Online (AAO). While not new, online encyclopedias and digital resources by state continue to expand their coverage, making them a quick and easy go-to for fact checking and finding new collections online.

Of course, digital content is limited and cannot replicate the depth of a physical archive or library. But re-assessing sources online and on the book shelf have become equally important. For more on the changing nature of archival research in the digital age, check out the Dec 2012 report, “Supporting the Changing Research Practices of Historians” by ITHAKA S+R.

What are other history resources worth a second look in 2013?